Students who have intellectual disabilities face an uphill battle after finishing school. Only 34% of adults with intellectual disabilities between the ages of 21-64 are employed after graduation. However, a partnership between the FSU special education program and Leon County Schools aims to address these challenges and help more individuals find meaningful employment.

On Tuesday, July 13, Jenny Root, assistant professor of special education, and Stacey Hardin, teaching faculty in the special education program, joined Florida Representative Allison Tant at the Adult Community Education (ACE) Summer Institute to talk about the partnership. This institute, which was started five years ago by Tant, helps young people with disabilities gain invaluable vocational experience, which can lead to gainful employment. It is the hope of Tant and the FSU faculty members that the institute and partnership can serve as a model for future transitional services around the state.

Expanding the Opportunities

The FSU special education program’s partnership with Leon County Schools is a beneficial one for both organizations. Currently, all of the teachers at the institute graduated from FSU’s combined bachelor’s/master’s pathway in special education. The director of the institute, Deidre Gilley, is also a doctoral student in the special education program and alumna of the master’s program. All of these graduates find meaning helping young adults in the local community gain new skills and improve existing ones. Furthermore, current graduate students help with teaching and assessment at the institute.

“Not only are we developing the workforce of attendees with disabilities, but through the university partnership we are also developing the workforce of those who are in the pipeline to be the next generation of teachers, counselors and therapists supporting successful transitions,” says Root.

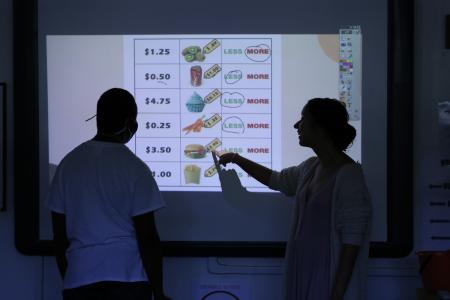

This pipeline of talented teachers ensures that young adults in Leon County have access to a great curriculum that helps improve employment opportunities. Each day for four weeks, attendees dive into four primary subjects aimed at helping them become more employable. These areas are workplace readiness, which includes things like time management, budgeting and how to apply for jobs; post-secondary transition; career exploration, which teaches how to look at different types of jobs based on what the individual is interested in and how to grow as an employee; and independence and living skills, including wellness concepts like nutrition, exercise and relationships, as well as rights and responsibilities.

This year’s summer institute welcomed 55 attendees from all around the area, with some individuals driving more than an hour each way for the opportunity. The long commute is indicative of the lack of availability for these programs, something that Root and her team hope to change.

“The institute is an amazing thing,” says Root, “yet this shouldn’t be extraordinary. It should be incredibly ordinary.”

To help make the case to create more of these institutes, Root is leading a team to evaluate the program. She hopes that when all is said and done, the ACE Summer Institute will serve as a model for other such programs around the state.

More Than Just Employment

While the institute helps individuals with intellectual disabilities become more ready for a job, the goal is more than just simple employment. Shockingly, it is legal to pay people with disabilities less than a minimum wage, due to a loophole in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which also established minimum wage. This loophole allowed employers to pay nearly 250,000 people with disabilities in 2016 on average $2 less per hour than neurotypical workers.

“The more intensive students’ support needs are, the less likely they are to obtain competitive, integrated employment,” Root says. “In turn, they are more likely to work in segregated settings for sub-minimum wages.”

Programs like the ACE Summer Institute are instrumental in helping these individuals bridge the gap between K-12 and the workforce. Root says the transition is often jarring for these individuals and their families. They go “from a K-12 experience of being entitled to supports and services that schools provide to being eligible for supports and services that they must seek out and manage. This can be very difficult if they are not equipped with self-determination skills necessary to advocate for themselves, set their own goals and make plans or adjust to meet those goals.”

Research shows when these individuals have paying, community-based jobs while they are enrolled in public school, there is a strong correlation to post-school employment success. And because students with intellectual disabilities can be in public school through the age of 21, they have more time to prepare for the rest of their lives and, hopefully, more time to find and benefit from these programs like the ACE Summer Institute.

The ultimate goal, says Root, is to help these individuals enjoy enviable adult lives, which means “a life you or I would want to live, and I am not sure why we would set a goal as anything less than that.”